Equine Health and

Disease Management

By

Dr.

Jack Sales, DVM

Copyright © July 2003

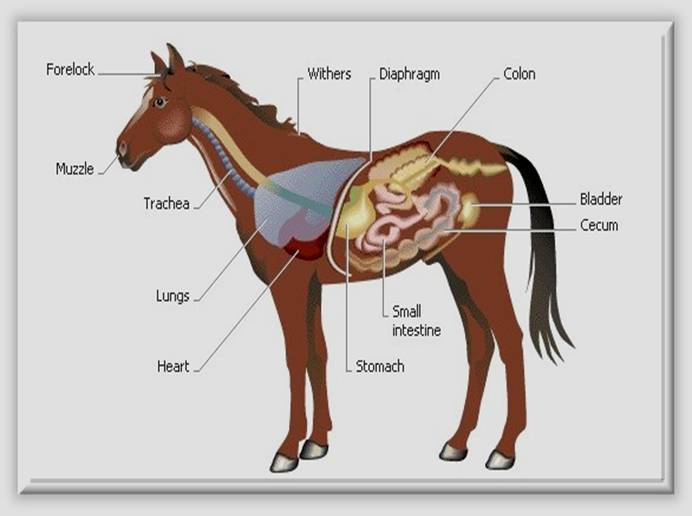

As we study Equine Health and Disease

management in this course we will want to become familiar with the internal

anatomy and functions of the horse as well as the external anatomy and

functional parts of the body. In each section, become familiar with the area on

the horse’s body that is involved in the disease process. This will make it

much easier to understand and remember.

Lesson 1

Musculoskeletal System

The first system we are going to study is the musculo-skeletal system. This will include the main muscles

and major bones of the body, with emphasis on the lower limbs. It is important

to realize the front limbs of the horse carry the majority of the weight of the

horse. The front limbs carry approximately 65 to 70% of the horse’s weight when

standing and, at times, even more when in motion. For this reason we will find

that the front limbs are the ones that seem to have more lameness problems in

the average horse. Of course, depending on the use of the horse, there are

times in which the hind legs are used more extensively, and in these cases we

see a number of hind limb problems. Think of the reining horse and how much

pressure is put on the hind limbs during different maneuvers.

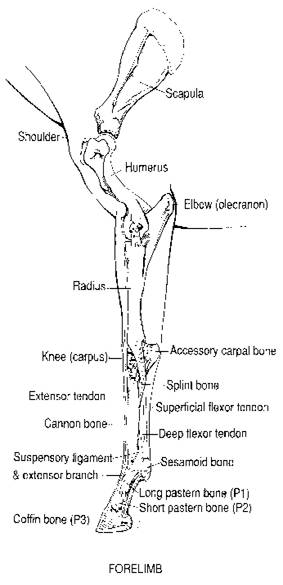

In order to study the lameness conditions of

the front and hind limbs, it is important the student have some knowledge of

equine anatomy. As we study the

different problems of the front and hind limbs, we will be referring to limb

anatomy. It will be necessary for you to

become familiar with the terms used as we study the particular area of the leg.

There will be diagrams of limb anatomy throughout our discussions of lower limb

lameness. It is important that as we identify some of the lameness problems of

the front and hind limbs, you can relate each problem to the area of the

anatomy that is affected.

When dealing with lameness problems in the

horse, it is important that we categorize each lameness problem as either acute, meaning that it was a sudden lameness that came on

very rapidly, or chronic, which would indicate a

problem or lameness that had a gradual and usually progressive onset. For

example, a sudden bone break or fracture would be considered an acute lameness

whereas a condition such as ringbone is considered a chronic condition that

comes on gradually over a period of months or years, and usually continues to

get worse and worse.

Let’s start our study of lameness problems in

the horse with the shoulder area of the horse’s front limb, and then continue

downward toward the hoof. One thing to keep in mind regarding lameness in the

horse is that most lameness is going to be seen in the lower limb area, from

the knee down. But for continuity, we

will start our study of front limb lameness in the shoulder.

Shoulder

Sweeny

This is a condition of the shoulder that is characterized by

atrophy (loss of muscle mass) over the shoulder blade. The muscles over the

scapula will atrophy (shrink or disappear) due to an injury to the nerve that

supplies these muscles. This nerve, the suprascapular

nerve, is usually injured by a blow to the area around the point of the

shoulder, and if the nerve is damaged severely enough, these muscles will lose

the innervation from that nerve and begin to waste

away. This will usually cause a mild lameness or funny way of going by the

horse, but many times the horse will learn to compensate for this muscle loss

and can be used for his intended purpose.

Looking at a horse with shoulder sweeny, you can easily tell that the shoulder on one side

is not full in appearance, and if you look closer, you can even see that the

skin is just covering the bone of the shoulder blade, with the spine of the

scapula (the bony ridge of the center of the shoulder blade) very prominent.

This is usually a permanent condition, in that this nerve, once damaged or

severed, does not grow back.

Fracture

of the Scapula

A fracture of the scapula or cracked scapula can occasionally

occur and is usually caused by as severe blow or kick over the shoulder blade.

All bone fractures show a sudden, usually severe lameness and it is usually

evident from severe swelling, where the fracture is located.

A horse that sustains a fracture of

the shoulder blade can usually be stall confined for a period if 3 to 6 months and healing will

usually be complete. Unless the bone break extends into the shoulder joint

area, the horse will normally heal without further lameness. A concept that you should keep in mind about fractures

or broken bones is that any break that extends into a joint area will have the

potential of causing a future arthritis of the affected joint after healing

occurs. So any fracture that extends into a joint area, unless surgically

plated or pinned by a veterinarian, will usually heal with continued future

lameness in that horse because of the arthritis in that particular joint.

Bicipital Bursitis

This is a condition that causes a lameness of the shoulder

area. The bicipital bursa is found on the front of

the shoulder joint, and when there is a blow to this area or there is a strain

to this area, the horse will show a short stride in the affected shoulder. You

can usually make the horse flinch to pressure directly over the point of the

shoulder from the front. Also if you pick up and extend the shoulder, the horse

may elicit a pain response.

Anti-inflammatory therapy (refer to the upper

and lower leg therapy section in this lesson) is helpful for this problem, and if

severe, a veterinarian can administer local injections (

refer to Injectable therapy in lesson 2) to

help resolve the problem.

Fracture

of the humerus

A bone break of the humerus is a

very serious injury. Oftentimes it is considered a life threatening injury.

Because the horse has numerous large

bones making up the front and hind limbs, we will talk about fractures of the

major bones of the horse’s limbs as a general subject.

All that will be discussed on this

subject applies to all the major bones of the horse’s limbs. The following is a

summary of most major bone fractures in the horse.

Fractures in the Major bones of Horses

Fracture = Broken

Bone = Broken Leg

Types

Of Fractures

n Simple Fractures

n

No displacement of bone ends.

n

Only one fracture line

n Compound Fractures

n

Broken piece of bone breaks through skin

n More serious because of introduction of

infection.

n Comminuted Fractures

n

More than one fracture line in a single bone.

n

More than two pieces of bone make up the

fracture

Other

Types of Fractures

n Compound comminuted fractures

Most

devastating type

Most difficult to

repair with good outcome

n Incomplete Fractures

n

Fracture line doesn’t go all the way through

bone

n Hairline fractures

n

Less serious

n

Usually only show mild lameness

n

Can warm out of lameness

n

Can turn into devastating complete, compound,

comminuted fracture if horse continues work.

Prognosis

( Outcome)

n Large bone fractures (Humerus,Radius, Femur, Tibia).

n

Very serious, possibly life threatening

n

Extreme swelling, and pain

n

Usually poor outcome

n Medical advances still lagging behind

n Fracture lines extending into joint

n Secondary arthritis very possible after

complete healing

n Future soundness unlikely

n Economics

n Great expense involved in attempts to

repair

n Horse’s weight a factor

n Adult horses weigh so much, often will founder

in opposite leg

n Horse’s temperament a factor

n May have to spend time in a sling

Osteochondritis Dissecans (OCD)

OCD is a disease condition in the horse

that can be found in nearly any major joint of the horse’s limbs.

We will discuss it here at the shoulder joint

and what you learn here will apply to OCD as seen in any other joint of the

front or hind limb.

OCD is

a condition that is seen as it develops in young growing horses. It is

associated with the areas of growth of the long bones and the long bones grow

at the ends of the bones close to the joints. Although the exact cause has not

been determined, research indicates that either a nutritional imbalance or a

change in the rate of growth (too rapid growth) could be the main cause. An

area in or around the joint loses blood supply and the area necrosis (dies),

which leaves bone chips, or cartilage flaps or bone cysts (holes in the bone)

in and around the joint. This causes the horse joint pain, which leads to

lameness, especially if the horse has started into training.

X-rays

are normally diagnostic to identify the problem and arthroscopic surgery may be

indicated to remove bone chips, spurs or bone cysts. The success of the surgery

is dependent on the amount of damage and the length of time the condition has

been there. Some horses respond to treatment well, some never fully recover,

developing a long-term joint arthritis that will plague the horse for his

lifetime.

Fractures

of the Radius or Ulna

Refer

to fractures of major bones above

Hygroma of the Elbow (Capped Elbow or Shoe Boil)

This is a condition caused by a blow or irritation

to the point of the elbow. Can often be seen in horse’s that lay on hard ground

with their elbows directly on the hard surface, or their heel or heel of the

shoe putting pressure on their point of the elbow. There is normally a swelling on the point of

the elbow that is slightly painful and full of fluid. It normally does not

cause lameness. This condition can become chronic where scar tissue is formed

over the elbow and it does not go away. In the acute case, a veterinarian can

be called out to drain and possibly inject the shoe boil,

hopefully bringing the swelling down The swelling may or may not return.

To prevent this from occurring in horses prone

to banging their elbow, a donut, which is a foam piece attached around the

pastern by Velcro or a buckle, provides a cushion which prevents the heel from

making contact with the point of the elbow.

Cellulitis

This condition can occur on the front or hind leg, but I

will discuss it here because it is commonly found in the forearm area. It is an

extensive infection usually caused by a puncture wound in the forearm area. The

puncture causes the infection to build and fester in the deep tissues of the

forearm and usually it will suddenly blow up (swell excessively) overnight. It

is hot to the touch and painful and usually causes a mild lameness or

tenderness of the leg.

If you

can find the area of initial penetration of the wound, make sure there is good

drainage (sometimes the wound is scabbed over and this traps the infection.)

Clean

the area with disinfectant soap and water and establish good drainage. The

horse will need a tetanus booster and normally your vet will recommend daily

antibiotics until the infection is under control.

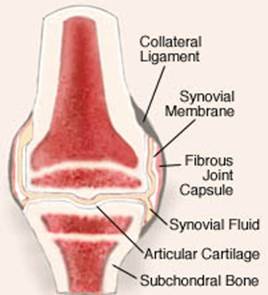

Degenerative

Joint disease (DJD) (Osteoarthritis)

This is a condition that can affect many of

the lower limb joints, and we will discuss it here as we begin to discuss the carpus or knee of the horse. What we say here will apply to

other joint areas of the horse’s limb that are affected by DJD.

DJD as associated with the knee joint of the

horse refers to the every day wear and tear that joints undergo, eventually

resulting in mild to severe arthritic changes within a joint. We are normally

talking about older horses when we talk about DJD, but it is important to

realize that this wear and tear starts early in the athletic horse’s career and

minor sprains and strains of joints in the early years can result in the start

of DJD. The problem may become severe

enough to end the young horse’s career.

Small chips in the knee joints can be removed arthroscopically and the horse will normally recover to

compete another day, but the damage that is done is never fully healed and

eventually more joint damage occurs which becomes additive. This process of additive repeated damage to

the joints is what is referred to as DJD in all its stages. Refer to

anti-inflammatory therapy and lower leg therapy for details on treatment of the

different stages of DJD.

Hygroma of the carpus

A blow to the front of the knee can occasionally occur

that can cause a large fluid filled swelling on the surface of the knee. It is

usually not painful, but can be unsightly and cause a restriction of knee

movement. It is necessary to contact a Veterinarian who will normally drain the

fluid off and inject with an appropriate anti-inflammatory medication and

recommend that the horse be stall confined with pressure wraps over the knee

until the skin attaches smoothly over the front of the knee.

If

exercise continues, the fluid will usually build back up due to action of the

knee.

Epiphysitis

This is a condition seen in the young

growing horse usually between six months and 2 years of age. Although it can be

seen in the knee, ankle (fetlock), or hock areas, it is normally a problem in

the knee area. The distal radial epiphysis (directly above the knee joint)

becomes inflamed due to imbalanced nutrition or excessively rapid growth

spurts. There can be some mild lameness.

There is normally an enlargement of the area

involved. This must be corrected by balancing the diet and/or slowing the

growth rate by cutting back on energy feeds such as grain and supplements. It is wise to notify a veterinarian to help

you manage this condition so no permanent growth abnormalities occur at the

epiphysis.

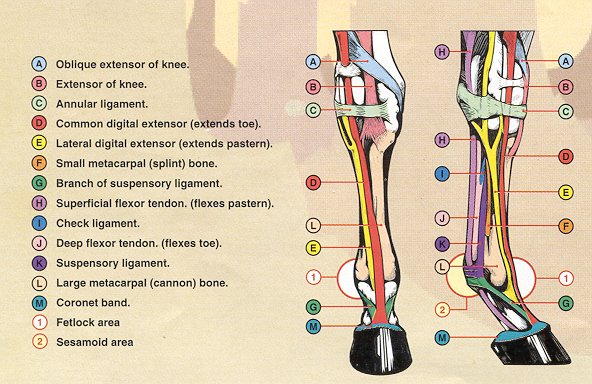

Moving down to below the knee we should

keep in mind that the anatomy in this area should be very familiar to us. If we

are not knowledgeable of this lower limb anatomy please take some time to

become very familiar with it. From the knee down, the anatomical structures are

the same as from the hock down. There is no muscle found below the knee or

below the hock. It should also be kept in mind that the blood supply to the

tissues and bone structure below the knee and hock is not very good which means

that healing of wounds or injuries is not very good either.

Bucked Shins (Shin Bucked)

This condition is seen in young horses in early training,

especially race training. The shin or cannon bone undergoes slow strengthening

as the horse gets heavier and heavier into training, adapting to the extra

concussion it is exposed to during this training process. Sometimes the

training can get ahead of the strengthening of the cannon bone and soreness and

inflammation of the front of the cannon bone occurs. The horse will be sore to

the touch, and heat and some swelling may be evident on the front of the shins.

This usually shows up initially as an acute condition, but if it is not

resolved it can turn into a continuous or chronic condition plaguing the horse

during much of his early career.

Therapy

to relieve the heat, pain and swelling is in order (refer to lower leg

therapies) and controlled exercise is also important to allow the cannon bone

strength to catch up with the training regime.

Splints

This is a similar condition seen in young

horses in training, and is caused by a strain of the ligament that attached the

splint bone to the cannon bone. The splint is usually seen high on the cannon

bone between the attachment of the splint bone and the cannon bone on the side

of the leg (inside or outside). It is painful when pressed on and usually warm

to the touch. Some firm swelling will also usually be found. As this splint

heals, calcium will fill in the area between the splint bone and the cannon

bone, making it stronger and able to withstand the strain. This may leave a

hard knot that is not sore or inflamed and this is also referred to as a splint , but technically would be called a dead (healed)

splint as opposed to a green (fresh or acute and sore) splint. Refer to lower

leg therapies for treatment protocols.

Fracture of splint bones

Occasionally the ends of the splint bones ( the lower inch or so) will break off or fracture. This

will cause a mild lameness initially, along with signs of inflammation (heat,

pain and swelling). These can be diagnosed by x-ray and the veterinarian will normally

recommend they be removed surgically. This is not a major surgery and the horse

will usually be able to return to training within a week or so. If they are not

surgically removed, a calcium bump usually forms in the area of the fracture

and may only slightly bother the horse, usually not causing a noticeable

lameness.

Bowed Tendon

The back of the cannon bone anatomy consists of the

superficial and deep flexor tendon, as well as the suspensory

ligament and the inferior check ligament. When the Superficial and/or deep

flexor tendon is strained or sprained or sometimes even ruptured due to excess

stretching, we refer to the swelling in this area as a bowed tendon. Bowed

tendons can be mild to severe and involve a small area or a very large area.

They are usually caused by excessive stretching of the superficial and/or deep

flexor oftentimes because of tendon fatigue coupled with continuous work.

Initially this is an acute injury with all the

signs of inflammation (heat, pain and swelling) and should be treated as an

emergency. (Refer to lower leg therapies). Depending on the amount of

involvement of the tendons, the horse usually needs from 3 to 12 months rest

for healing to occur. If there has been a substantial amount of tendon fibers

involved in the injury, the tendon usually heals with much scar tissue and the

horse is left with a larger, thicker tendon area (bowed tendon). This healed

tendon would be referred to as a chronic bowed tendon. The tendon is never as

strong or resistant to stretching as it once was, and is prone to re-injury

more easily, although with controlled training and exercise, many horses with

chronic bows can be very useful for certain endeavors.

Suspensory Ligament Desmitis

(desmitis refers to inflammation of a ligament)

This injury would be very similar to the bowed tendon, in

that the fibers of the suspensory ligament have

undergone excessive strain or sprain or rupture. A ligament has less ability to

stretch than a tendon, so it can be more easily injured with overstretching.

The suspensory ligament is found beneath the flexor

tendons, just behind the cannon bone, and attaches to the top of the sesamoid bones. It can be injured anywhere along its

length. Refer to lower limb therapies for treatment protocols.

Check Ligament Desmitis

(inferior check ligament)

This is an inflammatory condition caused by

a strain or sprain to the inferior check ligament which is located directly

behind the cannon bone in the upper part of the cannon bone. It is between the

cannon bone and the deep flexor tendon. This can be a difficult problem to find

because it is deep in this area.

Conditions and lameness from the fetlock (ankle) down to

the hoof all are associated with excessive concussion causing an inflammatory

process in the area of involvement. These conditions can be aggravated by poor

conformation causing excessive concussive forces in a certain area of the

anatomy. The following is a summary of the conditions and the anatomical area

of involvement. Keep in mind that the conditions discussed from below the knee

down to the hoof are normally seen in the front limbs, and are not seen as

often involving the lower structures of the hind limbs. As stated earlier, this is due to the fact

the front limbs carry 65 –70% of the weight of the horse and therefore absorb

the most concussion. All of the conditions below will be helped by referring to

lower leg therapies and anti-inflammatory treatments.

Osselets – refers to inflammatory changes occurring over the dorsal

and lateral and medial areas of the fetlock due to excessive strain.

Sesamoiditis

– refers to

inflammatory changes in and around the proximal sesamoids

due to excessive strain of the area.

Ringbone – Calcification

or new bone growth on the first, second, or third phalanx caused by excessive

strain or injury to this area. High ringbone refers to P1 or upper P2, Low

ringbone refers to lower P2 and/or upper P3. Articular

ringbone refers to new bone growth within the articulation (joint) whereas non-articular ringbone refers to new bone growth not involving the

joint surfaces.